Looking Back to See Ahead

Looking Back to See Ahead Concept Paper

Executive Summary

What is a workforce intermediary? This paper is an attempt to answer this and other questions. In a time where finding and keeping talent is a real issue, our purpose is to provide a history and offer solutions. In Edward Gordon’s White Paper titled America’s Meltdown: Why We Are Losing the Skills Wars and What We Can Do About It, he presents two linked problems in the United States: the growing gap between education and skills as well as a serious worker shortage. The lack of adequate education for much of the American population, which renders many incapable of filling the high-tech jobs of the 21st century, has put the U.S. at a disadvantage in the global skills war. Losing this war against other countries can result in an increased number of jobs going overseas which would only exacerbate the worker shortage the country faces due to the lack of qualified workers to fill vacant high-tech and technician jobs. While the white paper was published in 2003, there is no doubt that the country still faces both problems. The solution Gordon proposes to address both issues is to expand the education programs so that the education system better prepares students for various technician jobs that are facing labor shortages.

In this paper, we seek to take the lessons learned from various workforce intermediaries and nonprofit organizations such as the Private Industry Council in Boston, MA and the Metropolitan College, in Louisville, KY, as a means of addressing the problems that Gordon highlighted in 2003. Two important themes/take-aways of this concept paper are simplicity and wisdom. Using the lessons learned and wisdom from various organizations like those listed above, this paper provides a simple but realistic way to solve the problems that the United States faces.

This concept paper is organized into three sections: Looking to the Past; Looking at the Present; Looking Towards the Future. The first section (Looking to the Past) provides a brief history and a detailed summary of Gordon’s white paper that is mentioned above. This section serves as the foundation for this paper. The second section (Looking at the Present) begins by examining four questions/problems regarding supply and demand in the workforce and education in Louisville, Kentucky. The solution to education attainment and workforce shortage is provided by studying and examining the success of various career academies around the country. These academies/organizations include the Philadelphia Academies, Inc., Skillpoint Alliance, the Private Industry Council, the Metropolitan College, amongst others. We conclude this concept paper (Looking Towards the Future) by examining the work currently being done by Unique Staffing at the Thompson Hotel in Washington, D.C. as well as providing a model for the future. This model consists of career awareness in elementary school, career exploration in middle school, and career preparation in high school.

As discussed above, the bottom line of this concept paper is to recommend a simple but realistic way to solve both the growing gap between skills and education and the increasing worker shortage. By taking the lessons learned from the organizations and career academies, we gain the wisdom they have acquired and are provided with various simple models unto which we can adopt when working towards a solution. In conclusion, this paper attempts to provide a concrete example of how tomorrow’s future could be shaped by simple steps we take today.

Introduction

Years ago, I watched a video presentation of the top salesperson in the United States. Ben Feldman of New York Life shared his lessons learned on this video and all who wanted to succeed as he did could find one idea that could make them successful. As I watched I was struck by the simplicity of his message. He used the term “discounted dollar” to describe how life insurance proceeds were the cheapest dollars to pay death benefits. Writing a check at the time of death was “dollar for dollar” and borrowing was “dollars plus interest.” His conclusion was to use his ‘discounted dollar’ to pay the last expenses. As it is the least expensive means available.” Simplicity. When it comes to workforce development initiatives, we have witnessed many over the past 25 years that have made their mark. Those that have and are still in existence have a common thread of simplicity. The goal of this paper is to review some of the significant workforce initiatives in the past, examine the lessons learned and see if any of their elements can be used today and in the future. Ben also made another statement in the video that will be an underlying theme in this paper. At the end Ben said, “A fool learns from his mistakes, a wise person learns from others.” The underlying goal is to find wisdom from the experiences of others.

Looking to the Past:

The Workforce Investment Act

The Workforce Investment Act of 1998 signaled a change in the approach to workforce development. In shifting from a system of contract-based (organizational) to voucher-based assistance (individual) for training, this federal legislation changed the way many workforce development services receive support at the local level. This change also spurred initiatives from various foundations and advocacy groups such as the Annie E Casey Foundation (AECF) in 1995 which inspired new ways of thinking about practices and desired outcomes, particularly relative to serving the needs of disadvantaged job seekers. AECF created the Jobs Initiative, a multi-city, eight-year effort to identify improved workforce development approaches and to attempt to take those enhanced practices “to scale.” Out of this experiment came initiatives in Seattle and Milwaukee that provided lessons learned which are highlighted later in this paper[1].

America’s Meltdown: Why We Are Losing the Skills Wars and What We Can Do About It

One of the pioneering Futurist in workforce development is Edward Gordon. In 2003, he published a White Paper titled America’s Meltdown: Why We Are Losing the Skills Wars and What We Can Do About It. Gordon argues that there exists a link between education and skills in the workforce. He concludes that a lack of education contributes to Americans losing the skills war against other countries. Gordon emphasizes the dire need to address and mitigate this growing gap between education and skills as if left alone the country would face “chilling economic consequences” (3). Gordon goes on to propose a solution: expand the education programs so that they better prepare students for various technician jobs that are facing labor shortages.

After reading this white paper, there is little doubt that the skill/education gap is getting wider, which has negative implications regarding the U.S. economy and our ability to fight the current skills wars. Businesses have developed various tactics to combat the skills war, however, these tactics serve as short-term shortcuts that do little to shrink the skill/education gap, rather than long-term solutions. The results of this widening gap include high-tech jobs going “unfilled, while millions of badly educated Americans languish with low-pay, dead-end employment” (Gordon 3). Eventually, these jobs will leave the U.S. and go overseas to our chief competitors who are better preparing their citizens for the new economy of the 21st century. To sum it up, the U.S. is facing a serious worker shortage and on top of this, a lack of basic education skills (12th grade level in reading, application, and math) for almost half of the workforce that renders many incapable of performing various twenty-first-century jobs (Gordon). Not only does almost half of the US population read below an eighth-grade level, but businesses/employers also do not offer employees the chance to “develop the skills, training and education that might increase employee productivity and long-term company earnings” (Gordon 6).

The statistics provided in this paper are shocking. One may be left wondering how it is possible that nearly half the U.S. population reads below an eighth-grade level. The problem lies within the U.S. education system itself as it was not designed to educate the whole population equally. Instead, it focused on the education of some 20-25 percent of the population. Thus, many people in the U.S. receive a minimal education at best, which hinders their capacity to complete the ever complex and changing jobs of the 21st-century. Gordon concludes that the country “simply lack[s] enough well-educated people who have developed the successful critical thinking and technical skills required by a worldwide, high-performance workplace” (8). This problem (lack of well-educated people) can be attributed to a variety of factors including failure of local leadership to emphasize the importance of education and address education issues, the “legacy of half-hearted learning efforts,” failure of public and private schools to prepare students for employment, and the compartmentalization of education and employment. This compartmentalization has contributed to the fact that education does not continue into the workforce so that students are not prepared during school and continue to fall behind once they enter the workforce as there is little attention/time dedicated for training.

With the clear negative impacts that vacant technical jobs have on our economy, why is it that we are unable to fill these jobs. The root of this problem can be found in the structure of America’s 20th-century education system. Now, with the advancement of technology, more people need better education in order to fill 21st century jobs. This means that America’s “minimalist public-school system” is no longer enough, however, we have yet to fully reform the system (Gordon 20). To put it simply, there are not enough people with adequate higher education to fill the high-tech jobs that are increasingly being developed. In order to combat this growing shortage and deal with the issue, society must invest in both career and workforce education. Much focus has been put on getting students to college in order to obtain a bachelor’s degree as the best route to obtaining a good job. However, it is important to note that many future jobs don’t need a bachelor’s degree, they require adequate education and training. If we can unify “academic and career preparation into a more coherent system” in the school system, students (future workers) will be better prepared to enter the workforce and fill the vacant technician jobs (Gordon 27). Thus, the U.S. and its businesses should invest in the “intellectual capital” so that their employees become “better educated technical workers capable of redesigning job and work processes” (Gordon 18).

As a result of the technological revolution, many countries, including the U.S., face the problem of the widening skills gaps. The skills gap affects various aspects in our society including the loss of jobs to overseas workers, the success of the economy, and the standard of living in the U.S. One solution to this problem is expanding education programs in the U.S. so that they better prepare younger generations to have the skills needed for high-tech jobs. What the country needs is a “Second American Education Revolution” in which society no longer compartmentalizes work and education, and instead, schools have education-to-career programs that prepare students for real-world jobs. According to Gordon “education to a career means preparing a child for potentially multiple careers and job changes over a lifetime” (44). This revolution will take time and money, but the government and businesses must start thinking long term (invest in education) because the return on this investment will be significant. Gordon outlines some policy guidelines that he considers are bottom-line to make what education system he believes the U.S. needs, a “liberal-arts career academics.” These guidelines include skills standards, career concentrations, student choice, flexible career prep, shared economic investment, deciding who will teach, program management, and parental involvement. Ultimately, we must invest in education that represents the 21st century, because as stated the “vision of Workforce Education provides a sound scenario to improve career opportunities for both the current American workforce, and future generations…” (Gordon 54).

Although this paper was written almost two decades ago, the information Gordon conveys is still very relevant to the present day. If anything, the time has shown us how important career education is in giving the new workers the ability to fuel the U.S. economy to keep up in the skills wars. While the U.S. has not fully undergone a “Second American Education Revolution,” there are a handful of companies and organizations that have undertaken this task of adapting education programs oriented towards preparing people for the technician jobs. Companies such as Unique Staffing are working to address the issue and mitigate the effects presented by Gordon.[2]

New Approaches

Workforce Intermediaries (WI)

One new approach is found in a local/regional workforce intermediary. A workforce intermediary that is demand-driven is a business-oriented organization that seeks to match the needs of employers with the efforts of workforce development organizations, educational institutions, and government agencies. Like a film producer or a general contractor on a construction project, a workforce intermediary pulls together the right talent and experience to get the job done. Its objective is to ensure that employers have local job candidates available to them with the right skills when they need them. The workforce intermediary then makes sure that the employer and employee have the support system they need to keep the employee in the position, and to make the employment experience a mutually beneficial one. The workforce intermediary model has been used successfully in other cities and regions.

Among the best examples of the workforce intermediary model include the Seattle Jobs Initiative (www.seattlejobsinitiative.com). The Seattle Jobs Initiative (SJI) began in 1995 with the intention of connecting low-income and less skilled adults with businesses that had good-paying jobs. At that time, two of their main goals were to improve “job training programs and workforce development system reform” and improve the “outcomes for children and families by improving access and opportunities that would lead to economic self-sufficiency” (Seattle Jobs Initiative). It is now a nonprofit organization with the mission of creating opportunities and a path for people to obtain a living-wage, focusing largely on communities of color and low-income communities. SJI offers training programs in manufacturing, healthcare, diesel, maritime welding, and ironwork. A second example of the workforce intermediary model is the Wisconsin Regional Training Partnership (www.wrtp.org). The Wisconsin Regional Training Partnership (WRTP Big Step) was created in the Milwaukee area during the 1990s after various factors had contributed to a growing skills shortage in the area. According to their website, the nonprofit organization’s “response to this threat to economic growth and prosperity” was to create an industry-driven model “of pre-employment training for job seekers to qualify for family-sustaining jobs in the industrial sector” (WRTP | Big Step). WRTP focuses on helping residents find jobs and other opportunities in both the construction and manufacturing sectors. In 2003, the Sector Employment Impact Study was conducted about the WRTP. Some highlights of the study include: WRTP participants were more likely to find work and had a high retention rate, participants earned more than those who were not part of the program, and it was more likely/common that participants got jobs with benefits. Each of these workforce intermediaries has operated under a somewhat different model, reflecting the nature of the local economy and workforce. Other examples are the Capital Area Training Foundation of Austin (now Skillpoint Alliance) and the Boston Private Industry Council (www.bostonpic.org), which will both be discussed in depth below.

A supply-side approach to the development of workforce intermediaries is currently being led by the National Fund for Workforce Solutions (NFWS). This organization which is an Annie Casey, Hitachi and Ford Foundation lead initiative seeks to assist in developing 32 regional workforce intermediaries throughout the United States. In 2008, eleven (11) new cities/regions were selected for funding bringing the total to 20. NFWS seeks to improve employment, training, and labor market outcomes for low-income individuals. The Fund’s support will improve both the quality of jobs and the capacity of workers by promoting change at three levels: individual, institution, and system. The result: better jobs, better workers, and a better workforce development system (www.nfwsolutions.org). Over the course of the NFWS existence, it has worked with its 30 partner communities with the purpose of investing and scaling “innovative models that connect individuals to in-demand skills, generate good jobs, and help American business find and develop the talent critical for their success” (National Fund for Workforce Solutions). The key priorities of the organization for the next two years include advocating for community prosperity and opportunity for all, advancing healthcare’s frontline workers, providing better outcomes to low-wage workers, and more. Since its formation, the National Fund for Workforce Solutions has helped 92,000 workers, engaged over 7,500 employers to develop solutions, and catalyzed $315 million from the organization’s and funders’ investments.

In both examples, a workforce intermediary should have as its partners the following types of organizations: community colleges and universities, technical/vocational schools, workforce development organizations (to include community and faith-based organizations), and business partners (including the Chamber of Commerce, and trade and business associations) who will define the employment need. Typically, the WI is not a policy-making organization, such as federally supported Workforce Investment Councils or the local Chambers of Commerce. Instead, it is an on-the-ground, “in the trenches” organization that coordinates the workforce activities to respond to upcoming employment demand. Robert Giloth (editor of Workforce Intermediaries for the Twenty-First Century, 2004) indicates that “Great need exists to build regional and national infrastructure to support the development and expansion of WI’s, including venture funding for growth, benchmarking, human resource development, ongoing learning, and public policy. This infrastructure must be aligned with the goals and strategies of public workforce development systems.”

Are there new strategies that can guide the implementation of lessening workforce shortages?

Workforce Readiness Strategies

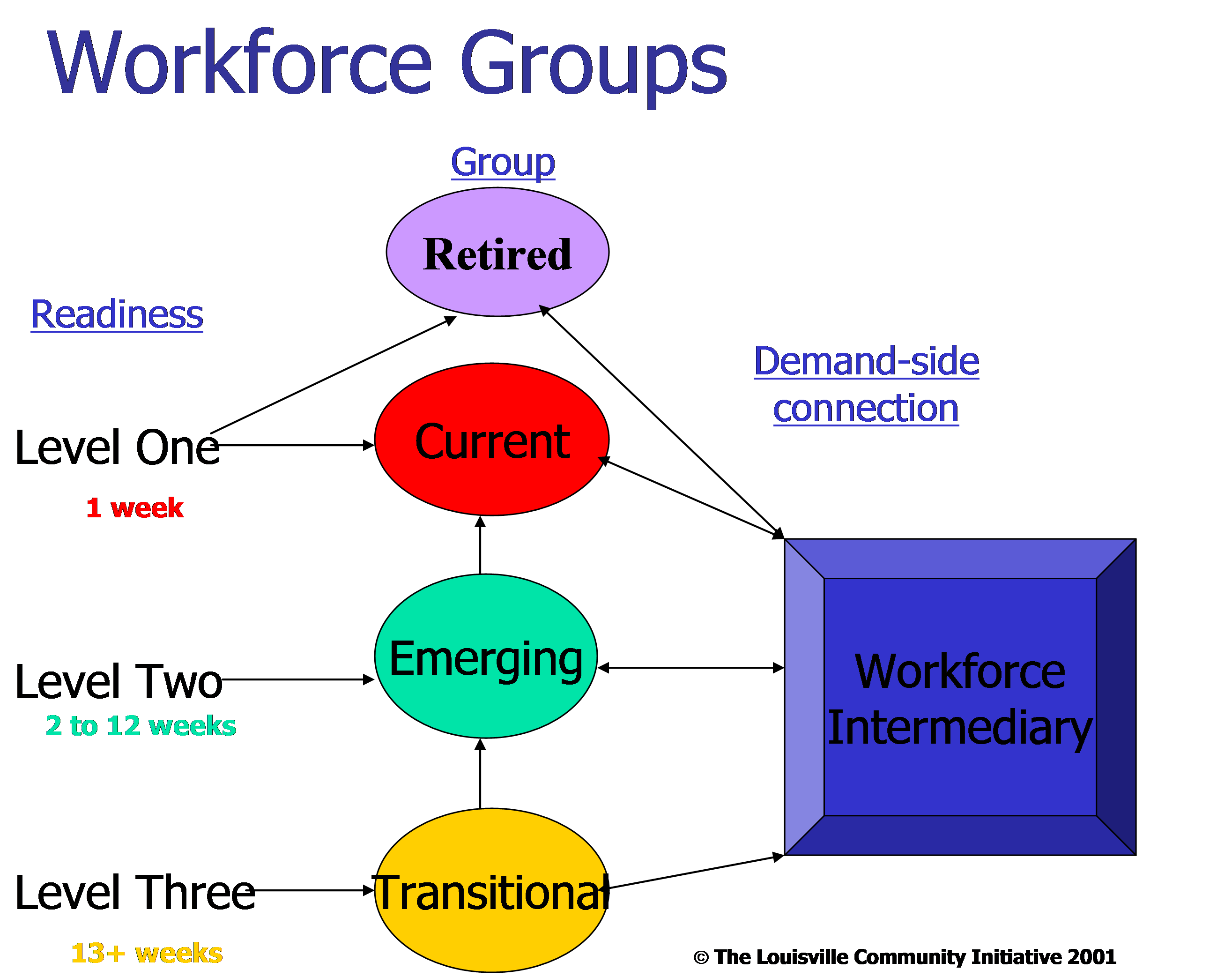

Cities such as Memphis, Tennessee, Austin, Texas, and Louisville, Kentucky have divided candidates into four workforce groups. Each group must have a strategy centered on the time it takes to prepare for a new work assignment. Senior citizens and those currently working (including those recently displaced) have the basic skills. They may need one week to become ready for a new work assignment. The strategy necessary for these two groups must include affordable opportunities to learn new skills or to keep skills current with the changing needs of employers. Those coming out of high school and to some extent college (the emerging workforce) need 2 to12 weeks to become ready. They need to learn the “language” of work as well as the culture of specific industries. The strategy necessary for this group must include real-world experiential education, expansion of school-to-work initiatives, and curriculum designs that meet the needs of employers. Those who are dropouts, ex-offenders, immigrants and welfare recipients (transitional workforce) need to “build” a work history as well as being prepared for a work assignment. They will need more than 12 weeks to become ready. The strategy necessary for this group must include short-term hands-on, real-world training that can result in employment opportunities in a short period of time (part-time or temporary employment). The training must address the basic soft skills and technical hard skill deficit that these individuals have and find innovative methods to deliver these skills. Below is an illustration of the workforce groups:

Each business or organization must approach the preparation of its candidates based on these workforce groups.

Looking at the Present: Louisville, Kentucky

A Problem of Supply: Educational Attainment

To jumpstart a new level of community conversation on raising educational attainment, Mayor Jerry Abramson invited school superintendents, college and university presidents, and business and civic leaders to an Education Roundtable. The challenge: to look at strategies to raise educational attainment and create transformational change. At the same time, Business Leaders for Education, organized by Greater Louisville Inc., called for the urgent need to respond to global competitiveness challenges. A main goal that came out of this commitment was to “move Louisville into the top tier among its peer cities by raising education attainment so that by 2020 at least 40% of working-age adults hold a bachelor’s degree and 10% an associate degree” (Greater Louisville Education Commitment 2). The members of the Roundtable signed the historic Greater Louisville Education Commitment, which lists five key objectives:

- Create and support a college-going culture

- Use the business community’s unique points of leverage to accelerate attainment

- Prepare students for success in college, career, citizenship, and life

- Make post-secondary education accessible and affordable

- Increase educational persistence, performance, and progress

From these key objectives, 55,000 Degrees was formed in October 2010 as a public-private partnership intended to bring about 40,000 bachelor’s degrees and 15,000 associate degrees by 2020, thereby making Louisville significantly more competitive with a highly talented workforce. Now, nine years after the historic signing of the Greater Louisville Education Commitment, we can examine the success of this partnership in achieving their goal of 55,000 Degrees.

To provide some background, in 2010 40.1 percent of the Louisville adult population had a college degree. By 2016, the percentage of adults with at least an associate degree increased to 44.7 percent, while the percentage with at least a bachelor’s degree increased to 35.7 percent. The original goal, as discussed above, was to have at least 50% of the adult population have an associate degree or higher. In 2016, the city was 5.3 percent away from its goal. By 2019, 42.9% of working-age individuals (age 25-64) had earned/received at least an associate degree and around 35% of which held a bachelor’s degree. It is important to note that these percentages are lower than in 2016 because they only consider working-age adults (25-64), not the whole adult population. While Louisville has made progress and moved closer to both their 55,000 Degrees goal and to their peer cities mean for college degrees, it is unlikely (looking at the trends) that the city will reach its goal within the next year (by 2020).

A Question of Supply: What Type of Degrees Are Needed?

The initiative launched to attain 55,000 degrees does beg a question. In what field or occupation is there a need? This is still a relevant question this initiative, along with others, must address. The assumption for this number of degrees is that getting a degree leads to higher economic incomes and a greater economic impact on our region. If the 2008 recession has taught us anything it is that having a degree without a job makes no impact on the community or families as a whole. There is also a philosophical issue that must be addressed. The apparent focus of 55,000 degrees implies that “education is an end unto itself.” It is “life-long learning.” Just get that degree and economic growth follows. That philosophy is supported by educational institutions, government, and many community and faith-based organizations. The business community, on the other hand, believes that “education is a means to an end, the end is a job/career.” It is not as much what you learn from getting an MBA from Harvard Business School as your ability to leverage your career opportunity with that degree.

While obtaining a degree can certainly benefit the recipient, simply having a degree is not enough. One must be able to get a job using their degree in order to have an impact on the community and the economy. As we have seen in Gordon’s white paper, just getting a degree doesn’t mean that economic growth will follow. The type of degree matters when looking at its impact on economic growth, as one must consider the capability of a person to fill vacant technician jobs using their degree. For example, if there are too many students with law degrees and not enough with technician training for the high-tech jobs in demand, this does little to boost the economy, as the needed jobs are still going unfilled. With that being said, when a degree is obtained it is assumed that the graduates have a certain level of proficiency in math, reading, and application skills which makes it easier for them to be trained for the high-tech jobs of the 21st century. At the end of the day, one thing that remains true is that having a degree without a job has little impact on the community (as stated above). Thus, it is important that degrees are chosen with the intention of using the degree to obtain a job. Below is a list of the types of degrees needed today (These are the majors that employers are hiring from) …

- STEM majors such as engineering (electrical, computer, chemical, civil, biomedical, mechanical, and petroleum), mathematics, physics, computer science, statistics, etc.

- Business/Finance, this includes management information systems, marketing, and economics

- Nursing

- Construction management

A Problem of Demand: Employer Workforce Shortage

More and more employers are finding it difficult to recruit and retain qualified employees. A good example of this is the healthcare field where finding nurses is still the number one healthcare workforce need. The 2008 recession injected more workers but many of them are not qualified for the needs of employers. In a CNBC article, it stated that there is a shortage of qualified employees to fill some 6.7 million job openings. According to the CEO Benchmark Report by The Predictive Index, talent optimization accounts for 80% of CEO challenges, thus talent strategy was rated second on the priority list. Talent optimization includes finding the right talent, aligning employees with business strategies, training, etc. As one can see by this report, obtaining talent and achieving talent optimization are key priorities. Having access to the right talent often comes down to the education of the public/workforce. Thus, an educated workforce is still an important factor to consider by businesses.

Is there a talent shortage? In April 2019, the National Federation of Independent Business (by William C. Dunkelberg and Holly Wade) reported that 38% of all owners had one or more unfilled job positions. This percentage is only one point lower than the record high. According to this report, 86 percent of those hiring or trying to hire found few or no qualified applicants for their vacant job positions. Additionally, “twenty-four percent of owners cited the difficulty of finding qualified workers as their Single Most Important Business Problem” (Dunkelberg and Wade 1). The report also mentions that business owners had more than double the number of open positions for skilled workers than for unskilled labor (Dunkelberg and Wade 1). These statistics come as no surprise as we transition away from an economy that depends on unskilled labor. Edward Gordon, (author of the 2010 Meltdown, Skill Wars and Future Work and Winning the Global Talent Showdown. How Businesses and Communities Can Partner to Rebuild the Jobs Pipeline) says that there is a shortage and the shortage is worsening. He indicates that there are economic and cultural forces that have combined to produce this shortage: a worldwide demographic shift and a broken talent-preparation system. Gordon’s claims are proven by the statistics offered by the National Federation of Independent Business as mentioned above.

A Question of Demand: How Significant is the Shortage?

The baby boomer generation (1946 to 1964), which represents approximately 48% of the workforce, is retiring. The U. S. Department of Labor predicts that between 2010 and 2020, 70 million Americans will retire, but only 40 million will enter the workforce. Overseas governments such as Italy, Germany, the United Kingdom, and Australia are paying “baby bonuses” in anticipation of this “baby bust. (“Demographics; Baby Bonuses and Other Solutions”, Herman Trend Alert, August 8, 2007). According to a member of the human resource department of E. ON (a diversified energy services company), nuclear-powered utility companies in California are beginning to identify and recruit talent in middle school.

The Achilles heel of America’s economy is its undereducated workforce. More than 90 million U.S. workers currently lack the reading, writing and math skills to do their jobs properly. National Adult Literacy Assessments were conducted by the U.S. government in 1992 and 2003. They showed little if any literacy progress. The conclusions drawn by the National Adult Literacy Assessments are supported by more recent data as well. According to “Skills of U.S. Unemployed, Young, and Older Adults in Sharper Focus: Results from the Program for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies (PIAAC) 2012/2014,” The United States scored closely to the PIACC international average score regarding literacy. However, the results revealed that there was a larger disparity between the top and bottom performance. Additionally, the U.S. performed below the PIACC “international average in numeracy and problem solving in technology-rich environments” with a smaller percentage at the top levels and a larger percentage at the bottom (5). Numeracy can be defined as ‘“the ability to access, use, interpret, and communicate mathematical information and ideas, to engage in and manage mathematical demands of a range of situations in adult life’ (OECD 2012)” (“Skills of U.S.” 2). The Washington Post argues that “approximately 32 million adults in the United States can’t read, according to the U.S. Department of Education and the National Institute of Literacy. The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development found that 50 percent of U.S. adults couldn’t read a book written at an eighth-grade level.”

For national security reasons, national defense contractors must also employ U.S. citizens to build aerospace and military hardware. With increasing shortages of qualified U.S. tech workers, many Pentagon staffers and defense contractors want Congress to eliminate the so-called Berry Act restrictions to gain access to non-U.S. talent. According to Gordon the long-term consequences of doing nothing over the next decade to reduce the talent shortage will create an emerging U.S. “techno-peasant underclass” that will be trapped in low-wage service jobs. As Gordon stresses, there must be an education revolution that better educates each student and prepares them for 21st century jobs. According to the Alliance for Excellent Education, high schools need to do a better job of preparing students to be successful in both college and careers. The Alliance states that “many of today’s high schools are not providing students with an engaging experience that is relevant to the workforce and that integrates partnerships with industry and higher education.” By reforming these schools and emphasizing advanced literacy skills we can better prepare the future workforce to succeed in our fast-paced economy. While “the total number of students who do not graduate from high school has declined, from 1 million high school dropouts in 2008 to approximately 750,000 dropouts in 2012” (Alliance for Excellent Education), there is still a declining interest in Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics (STEM) in U.S. teenaged boys (from 36 percent to 24 percent) and a continued low interest (11 percent) for girls (Junior Achievement USA).

A Solution to Educational Attainment and Workforce Shortage: A Community Intermediary (Career Academies)

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

In Philadelphia, Pennsylvania beginning in 1968, another model has been successful that combines the traditional education system with active involvement with business. The Philadelphia Academies, Inc (PAI) model is based on the assumption that it can significantly change life and economic outcomes for young people by motivating them to learn through their own interests and real-world, career-connected experiences and curriculum. Embedded in the model are three core activities – programming that motivates, the active development of networks with caring adults, and local advocacy at a policy level for instructional and structural changes in secondary education. Their model has been adopted by 8,000 schools around the country. A goal of PAI is to “support career-connected learning in our partner schools. Bringing together schools, industry, and higher education, we leverage our relationships and knowledge to transform learning so that young people are prepared for in-demand careers and/or post-secondary education upon graduating high school” (Philadelphia Academies Inc.) PAI serves as an intermediary, bringing the financial and human resources of the business community into Philadelphia public schools, providing work and life readiness skills, making connections to internship experiences, and offering scholarships that provide a path toward a productive life. PAI engages over 400 volunteers from the local business, labor, non-profit, and higher education communities in improving education and building 21st Century skills for Philadelphia public high school students.

In the last few years, the structure of PAI has been reformatted. The organization now has six core career-connected learning strategies: Work Based Learning (WBL), Career Pathways, Career Academies, Pre-Apprenticeship Bridge Programs, Data Supports, and Freshman Success. The focus has expanded to offer opportunities in elementary, middle, and high schools. PAI has become a national model that has been the subject of various research studies, such as this concept paper, and has paved the way for various organizations around the world. PAI serves over 4,500 students across 14 different schools (12 of which are high schools) and works with roughly 300 teachers. The case of Roxborough High School can be regarded as a success, and the results highlight the impact of PAI. In 2011, Roxborough High School enlisted the help of PAI in using their career academy model. By 2015, Roxborough’s attendance rates were 90% (up 15%) and its graduation rate was nearing 80% (up nearly 20%). Additionally, out-of-school suspensions decreased, and the college-going rate increased roughly 36% between 2012-2015. As of 2015, the school was working with PAI, to create a work-based learning program and have college exposure for students.

PAI addresses both the problem of supply (education attainment) as well as the problem of demand (employer workforce shortage) that were discussed earlier in this concept paper. The nonprofit helps to bring together schools, higher education, and industry (businesses) so that students are better prepared for in-demand careers, such as the high-tech jobs discussed by Edward Gordon in his white paper, as well as post-secondary education. It serves as an example of the success of school-to-work programs.

Austin, Texas

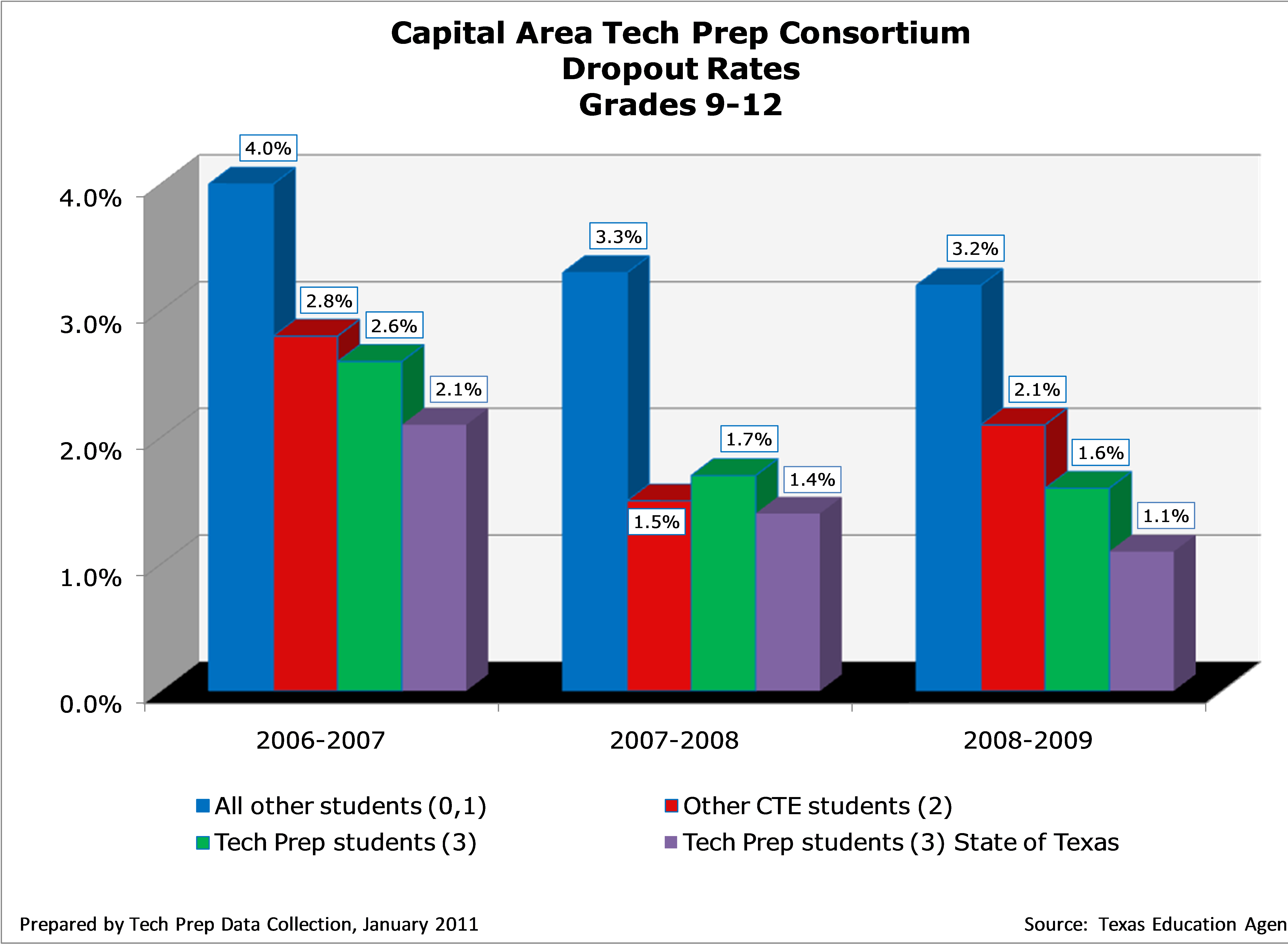

Austin, Texas developed a model that focused on combining academics that lead to a diploma and technical education that leads to a career. The Capital Area Tech Prep Consortium is a way to start a college technical major in high school. In a Tech Prep program, you begin your course of study in high school and continue in a community or technical college. The result is a certificate or associate degree in a career field. Tech Prep programs combine the academic courses needed for success in college AND technical courses that begin to prepare you for a career. Businesses are actively involved in Tech Prep. A benefit to Tech Prep is its impact on dropout rates. Below is a chart that illustrates the positive impact this program has on keeping youth in school.

A unique feature of the Capital Area Tech Prep Consortium is its ties to middle and elementary schools. There is a focus on Career Awareness in elementary school, Career Exploration in middle school and Career Preparation in high school. In addition, grades, attendance and graduation rates improve over those in the “traditional” K-12 system.

The Capital Area College Tech Prep Consortium released its last report in 2011 for the 2010-2011 school year. This is as a result of the lack of funding for the program in the upcoming years. Even though this prep program is no longer funded; it still has had an impact on the city of Austin. Since its formation in the 1980s, the program has expanded to include 29 school districts, active articulations in 21 college program areas, 80,000 students enrolled in Tech Prep courses, and the escalation of enrollment and credit collections in the last several years (increasing at 38% and 18% respectively). In their last report, Capital Area College Tech Prep Consortium stated that “during the 2010-2011 academic year 4,161 students were granted college credit at Austin Community College (ACC) for 6,065 articulated courses they took in high school… (11).” Of those students, about 19% have chosen a college major in a field the same as their course of study in high school” (“Capital Area College” 11). This number is nearly double the percentage of the previous year.

The Capital Area Tech Prep Consortium addressed both the problem of supply (education attainment) and the problem of demand (employer workforce shortage), that was discussed earlier in this concept paper. Not only did it give students an education that will prepare them for 21st century jobs, but also provided an avenue unto which these students could combat the employee work shortage in fields related to a technical major. Additionally, it serves as a potential response to the question of supply (what types of degrees are needed?), as it prepares students for a technical major which would be a useful degree for the 21st century workforce.

The Capital Area Training Foundation

The Capital Area Training Foundation was founded in April of 1994 when, then Mayor, Bruce Todd called upon the Greater Austin Chamber of Commerce Task Force on Apprenticeships, and Career Pathways for Austin to create a solution for the lack of apprenticeship and craft training in the City of Austin. A task force was created to focus on the establishment of a nonprofit, industry-led, self-governing organization to promote and guide the development of skilled trade training efforts in Austin. And thus, the Capital Area Training Foundation was chartered.

That Foundation grew into Skillpoint Alliance and has since become the premier choice in the city of Austin for rapid workforce training. Skillpoint has been featured in economic reference books, Economic Development in American Cities: the Pursuit of an Equity Agenda and Inequity in the Technopolis: Race, Class, Gender, and the Digital Divide in Austin and has been named one of the top ten job training programs in the country by Jobs for the Future and the U.S. Chamber of Commerce.

The Capital Area Training Foundation (CATF) was an employer-driven intermediary that supports employer priorities in school-to-career activities and workforce development. It was created based on the view that employers are more likely to participate in specific education reforms if they can do so through an employer-led entity. This explicit grounding in the private sector sets CATF apart from many local partnerships, which are often dominated by organizations of schools and educators.

CATF acted as a broker between employers and local schools in the Austin, Texas region. Staff members, together with volunteers, support the work of industry-sector steering committees. These committees are responsible for engaging employers in designing career pathways; providing work-based learning experiences to students and teachers; and linking employers directly with schools and postsecondary institutions.

About half of CATF’s efforts concerned youth development through school-to- career support, which is the focus of this case study. CATF also placed a priority on adult transitions to work, especially welfare-to-work projects. The organization engages in similar strategies for both youth and adult workforce issues.

In its four-year history, CATF was a catalyst for change within schools and employers across the Austin metropolitan area.

Key Lessons

- Brokering is a new and necessary function.

- Work with and through existing intermediaries and practices.

- Go in the direction that employers want, using the vehicle of industry clusters to define direction and articulate employer goals.

- Work on a regional level.

- The key to sustainability is local support.

Skillpoint Alliance

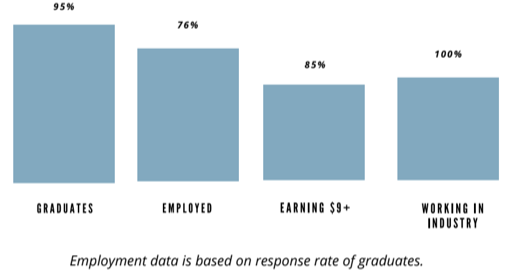

Skillpoint Alliance is a 501 (c) 3 workforce development organization that provides in-demand workforce training to vulnerable members of Central Texas communities. Founded in 1994, as the Capital Area Training Foundation, to address the lack of apprenticeship and craft training, it serves as a connection with local industry partners and offers professional training and education opportunities. Skillpoint Alliance is known for rapid workforce training. The organization adapts program offerings to represent/accommodate workforce needs in the region and has impacted over 140,000 Texans. The organization targets underrepresented populations who have barriers to employment, such as little to no work history, to help them become more self-reliant and earn a livable wage. Their mission is to “provide a gateway for individuals to transform their lives through rigorous skills-based training and education.” The vision of the organization is that “every Central Texan will have access to a successful career pathway.” In its Gateway Austin Area Training, programs include nurse aide, pre-apprentice electrical, HVAC technician, pre-apprentice plumbing, carpentry, and culinary arts and basic construction. Training prepares participants for entry-level employment in as little as 4-8 weeks. Courses involve a mix of hands-on and lecture-style instruction. The instruction translates to tasks and skills graduates will be asked to perform daily. During the 40 hours per week in class, students learn skills such as succeeding in a job interview, planning for their career, and preparing a resume (Skillpoint Alliance).

According to their annual report (2018), continuing education enrollment increased from 14% in 2017 to 30% in 2018. Following the graduation of their students “Skillpoint saw an increase in employment within the industry graduates trained for, hourly wage earnings, and enrollment into a continuing education or apprenticeship program than years prior due to industry involvement throughout each program.”

On top of these successes, Skillpoint has a partnership with a local juvenile detention center in which offenders are selected for construction and/or culinary programs. Lastly, with their WACO Programming, the organization can get more individuals who may be homeless, unemployed, or re-entry citizens into the workforce.

Boston, Massachusetts

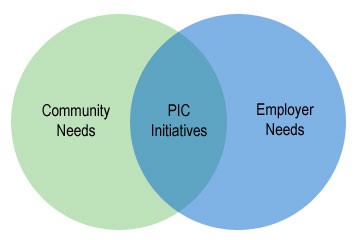

Boston’s Private Industry Council (“PIC”) was founded in 1979 as a business-led organization, partnering with education, labor, higher education, the community, and government, to provide oversight to public workforce development programs. Their mission is to strengthen Boston’s communities and its workforce by connecting youth and adults with education and employment opportunities that prepare them to meet the skills demands of employers in a changing economy. The goal of the PIC is to “increase dramatically the number of students, both youth and adults, who earn the credentials necessary to secure career-oriented employment and achieve financial independence with the opportunity to advance professionally. As the city evolves as an international hub for knowledge-based industries, Mayor Walsh and the PIC want to ensure that Boston residents are prepared to become the workforce of the future” (Boston Private Industry Council). PIC initiatives thrive on the synergy created when business needs and community needs overlap. As an intermediary, the PIC plays four interrelated roles:

- Convenes multi-sector collaborations

- Connects employers with schools and students with jobs and internships

- Measures progress on key indicators such as dropout rates and college completion rates

- Sustains the efforts to create career pathways for students and talent pipelines for employers

Beginning in 1982, PIC has served as the convener of two major initiatives:

- The Boston Compact, a school reform agreement among the Boston Public Schools, business, higher education, the Boston Teacher’s Union, and the Mayor.

- Boston’s Workforce Investment Board, a federally authorized oversight body that approves spending and measures the effectiveness of publicly funded workforce development programs, in partnership with the Mayor of Boston.

The PIC agenda is designed to meet the needs of both the community and employers. The strategy is to create pathways to career success through partnerships that emphasize education and training while sustaining a dynamic relationship among employers.

The PIC’s partnership with the employer is essential to connecting Boston’s youth and adults to education and careers in the mainstream economy. PIC strives to generate both workplace experiences and jobs for high school students. The Employer Organizing Team is organized by industry groups that include healthcare, financial services, law, retail, higher education, and utilities to effectively broker these employer relationships. PIC and its committees identify labor and skill shortages that are key to Boston’s economic health. PIC is comprised of prominent business, labor, higher education, government and community leaders.

One of PIC’s functions is to craft education and workforce initiatives that focus on residents. The result is a win-win situation. Employers develop the workforce they need, and Boston residents gain access to career opportunities and higher incomes.

According to their annual report, the process they follow is…

“PIC career specialists identify, prepare, and match Boston public high school students with paid work experiences in professional environments they would not be able to access otherwise. They assess student motivation and reliability throughout the year based on participation in workshops and career exploration opportunities. The employer engagement team recruits new employers and assists participating employers with interview schedules, hiring processes, and supervisor recruitment” (2).

In 2018, 2,520 students obtained summer jobs through PIC, 147 private-sector employers hired a student, and over $9 million in employer-paid wages were generated. When considering the question of “what type of degrees” PIC answers with their C-Town Tech pathway which allows students to take classes at a local community college, work in tech-focused internships, and more.

Additionally, PIC is committed to re-engaging young adults that have left school or fallen behind through the Re-Engagement Center (REC). So far, 3,092 students re-engaged through Boston Public Schools (BPS)-PIC collaboration since 2006, 824 REC students have earned a high school diploma, and the annual dropout rate is 3.6%, the lowest on record (“Boston Private Industry Council 2018” 4). When it comes to postsecondary success, as part of the Success Boston program, PIC “coaches connect students with college and community resources, while providing them with guidance and support” (“Boston Private Industry Council 2018” 6). According to the annual report, 51.6% of first-year college enrollees from the Boston Public Schools (BPS) Class of 2011 graduated in 6 years, 70.8% of BPS Class of 2016 graduates enrolled in college within 16 months, and 521 community college and transfer students were coached by the PIC (6). Regarding Boston’s Workforce Development System: 15,515 job seekers served at Boston career centers, 761 employers held job fairs and recruitment events, and the average wage upon employment for career center customers was $21.61 (“Boston Private Industry Council 2018” 8). Lastly, for employer engagement, the PIC connects Boston students and educators to the innovative businesses and transforming industries that are rooted in Boston; this is done through increasing high school internships and other work-based learning opportunities. According to the annual report, a 46% increase in Professional and Technical Services employment in Boston occurred over the past 10 years, Massachusetts teen employment rate was down from 50% in 2000 (to 32%), and there were 657 PIC students in STEM-related internships in summer 2018 (10).

Louisville, Kentucky

The Metropolitan College, located in Louisville is a Kentucky partnership between UPS, University of Louisville, and Jefferson Community & Technical College. It was founded as a joint education-workforce-economic development initiative. This education program served as an incentive package that helped convince UPS to remain in Kentucky and expand its overnight air hub. It offers “post-secondary education opportunities for eligible employees in the Next Day Air operation at UPS WorldPort.” It serves as an example of a solution for the “elimination of financial barriers to higher education for residents of Kentucky and a proven model for workforce retention” (Metropolitan College). So far, this partnership has “helped more than 17,000 students pursue free post-secondary education and on-the-job training while reducing workforce turnover rate from over 70% to less than 20% and “more than 5,500 individuals have earned over 9,200 certificates, associate, bachelor and graduate degrees” (Metropolitan College).

How Does it Work? – (Metropolitan College)

- Work 3rd shift as a part-time package handler at UPS Worldport in Louisville, KY

- Get paid a regular wage from UPS

- Paid tuition—up to full-time undergraduate, in-state rate—at either the University of Louisville or Jefferson Community & Technical College each semester

- Eligible for bonuses based on your academic progress ranging from $350 to $1,400.

- Can get book reimbursement money each semester to help offset the cost of books and software.

Quick Stats (Provided directly from website-Metropolitan College):

- Student retention on the job has increased from an average of 8 weeks prior to MC program inception to 195 weeks currently

- Work retention of UPS-MC participants in 2015 was 89% compared with 39% for non-MC participants working the same shift

- Percentage of students working at night for UPS has increased from approximately 8% prior to MC program inception to 37% currently (35% was the original goal)

- Fall 17 to Fall 18 student retention in school was 54% for JCTC participants and 55% for UofL participants (these students completed fall 2017 coursework, remained employed and returned in the fall of 2018)

- As of Fall 2018:

- 5,583 students (participated in MC for at least one semester) have earned one or more credentials totaling 9,220 as of Fall 2018. Duplicated student numbers and total credentials earned:

- 1,236 students earned 2,758 certificates

- 1,925 students earned 2,362 associate degrees or diplomas

- 3,469 students earned 3,646 baccalaureate degrees

- 419 students earned 454 masters or other graduate degrees

- Top 10 Majors for Fall 2018 by School

- JCTC: Associate in Arts, Associate in Science, Aviation Maintenance Technology, Business Administration, Criminal Justice, Computer & Information Technologies, Health Science Technology, Education, Engineering, and Automotive Technology

- UofL: Arts and Sciences: Undecided, Nursing: Lower Division, Psychology, Communication, Criminal Justice, Business: Undecided, Computer Information Systems, Exercise Science, Biology, Marketing

Washington D.C.

Forest City Washington (now Brookfield Properties) is a nationwide real estate development and management company that is currently redeveloping 42-acres in Washington D.C. According to NAIOP “to ensure diversity among the contractors, the firm instituted a voluntary mentor/protégé program” and subtracted parts of their projects to small local disadvantaged contractors (1). Additionally, Forest City launched its own workforce intermediary program to “recruit, train, hire, and retain local residents” (NAIOP 1). The FCW WI team leader was Andre Banks.

Andre Banks along with his team that consisted of John Fleming from Unique Staffing, Darryl Dennis of wire2net, and Andre Bryan of APB and Associates outlined the problem faced and came out with a solution. The Problem: “More and more employers are finding it difficult to recruit and retain qualified employees. The recession injected more workers but many of them are not qualified for the needs of employers” (1). The Solution: “To “build a bridge” that better connects District residents to employment opportunities offered by Harris Teeter and other tenants on D Parcel” (1). The two-part strategy, examining the capacity of the local community to recruit, train and retain candidates and (second) assessing the commitment of Harris Teeter to hire and retain District residents, has three phases (Forest City Washington Workforce Intermediary Digest (Draft 2)).

There were two main goals for this project: one; “to have at least 35 percent of local businesses get their fair share of contracting work and to make sure that D.C. residents get hired” (NAIOP 1) and “to match local residents with retail jobs and achieve a 70 percent retention rate” (NAIOP 2). One of the two vehicles used to enable this to happen was the mentor/protégé program with the general contractors it hired. The results of this mentor/protégé program can be found below.

- Results: Local Business target exceeded

- Waterfront Park—56 percent of work went to a CBE (Certified Business Enterprises

- Foundry Loft Apartments—44 percent

- Pedestrian Bridge—45 percent

- Boilermaker Shops—53 percent

- Lumber Shed—57 percent

Not only did Forest City’s program exceed its target, but in some cases, the smaller contractors became “the prime contractors for these projects, and that was the goal all along”’ (Brown).

The other vehicle was a “workforce intermediary to recruit, train, hire, and provide job coaching for local residents” (NAIOP 2). The results of the workforce intermediary at the Harris Teeter store can be found below.

- Results: 82 percent retention rate

- More than 300 local residents hired, which represents a 1 percent reduction in the District’s unemployment rate

- $410,958 additional tax revenue for Washington, D.C.

- $693,600 potential work opportunity tax credit available to employers

- $736,661 cost per hire savings to employers

The efforts by Forest City have a ripple effect in the city. According to Steve Dubb “hiring local firms and residents has a local economic multiplier effect” (NAIOP 4). This can be seen in the case of staffing Harris Teeter. 82 out of the 125 candidates from Forest City rolls were hired by Harris Teeter and the retention rate was 82 percent. The retail industry often struggles with retention of its workers; hence Forest City’s workforce intermediary shows a potential solution to the problem of retention. So far 289 people were placed into jobs which raised the city’s employment by 1 percent.

According to Andre Banks, trust must be regained in the community to be successful with these projects. This is because that trust will translate “into work opportunities for residents” (NAIOP 7). Additionally, the NAIOP article outlines three key steps when trying to launch diversity programs

- Identify local allies and partners

- Build community trust by holding neighborhood meetings

- Work with trusted local partners

Looking towards the Future:

Brookfield

Unique Staffing (www.workforceintermediaries.com) will be working to staff the Thompson Hotel that opens in December of 2019. There are three phases to this project: (1) planning and designing, (2) organizing, constructing, directing, and (3) maintaining. Phase one consists of defining the needs of the Thompson Hotel, identifying and meeting with local centers of influence, and meeting with and evaluating Supply-Side Partners. In phase two, employer-hiring needs with trainer and supply delivery must be aligned. Phase two also consists of the directing phase which includes “actual testing, recruiting and placement of the first hires for the Thompson Hotel” (“Brookfield Scope of Work” 2). In the last phase (Maintaining), the goal is to hire 51% from the District and have a 70% retention rate for 6 months.

Model for the Future

A visit to the Capital Area Training Foundation in Austin, Texas in 2001 generated ideas that may be relevant for the future as our country seeks models to develop the workforce for the future. Their school systems had a “dual-track” approach that ran parallel to the traditional public-school system model that ends with a high school diploma. You had “career awareness” in elementary school. Businesses systematically came in and introduced elementary school youth to careers in all fields from the academic to building trades. You might consider it a business form of “show and tell.” Middle schools had “career exploration.” These youth witnessed surgery in a hospital, flew aircraft in a flight simulator and spent a day “shadowing” a parent or family friend at work. The purpose of the time spent was to see and examine activities that were a part of a career. “Career preparation” began in high school where exposure to programs and courses at the community college were offered. Dual credit was available where select courses in high school were also accredited by the community college. Each student could graduate with 15 hours of community college credit. Summer internships were also important to high school juniors. At the end of that junior year, youth could participate in a summer internship in the industry of their choice. They would work full time that summer and part-time their senior year. At graduation, they had three career paths:

- They could move from part-time to full time in their career field at their current place of work

- They could continue part-time and attend the community college where they had accumulated 15 hours of credit from high school or

- They could go to college full time and work the following summer in their previous summer’s internship

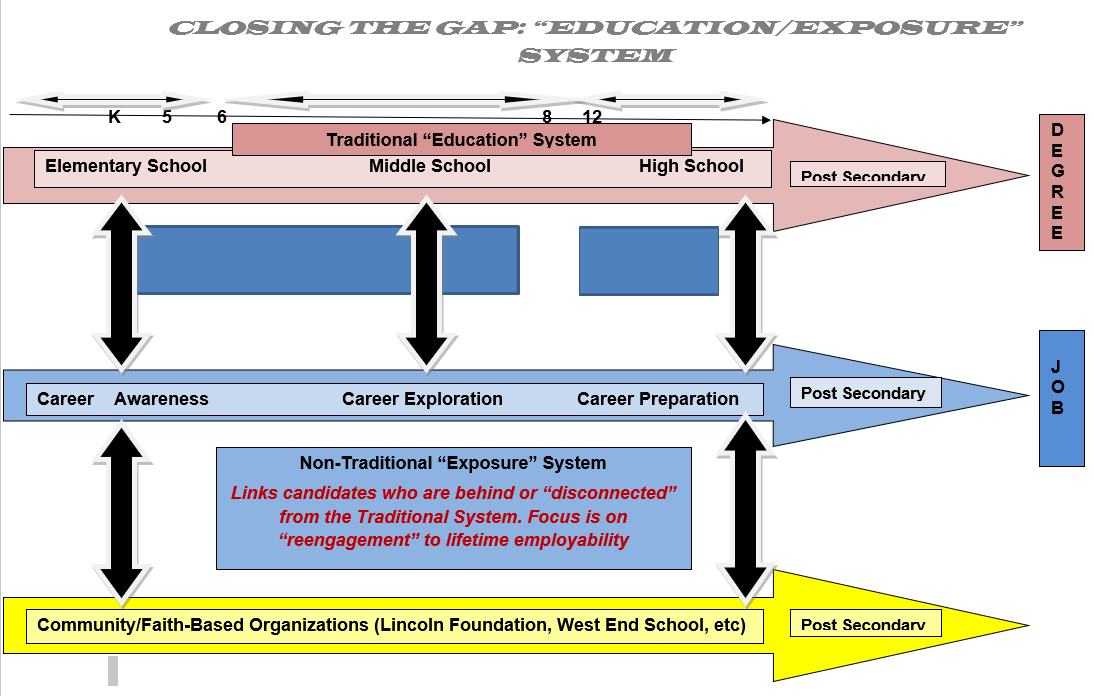

That model can work, but what happens to youth who, for whatever reason, “falls through the crack” and drops out of school? This is where the third level comes in. This level consists of a network of community and faith-based organizations that provide a “safety net” that catches these youth, provides them the support and resources needed to recover, and reconnects them to their community and careers that lead them to self-sufficiency. This network is bound together by a community “intranet” that connects them to the support needed electronically. A diagram or illustration is provided below:

Diagram: “Closing the Gap”

Closing Comments

Our communities can provide innovative solutions such as the “Closing the Gap” model if we are committed to solving the problems of workforce development. We can learn not only from our mistakes but from others as those mentioned in this paper. The time is now to “look back to see ahead.”

Work Cited

Alliance for Excellent Education. Alliance for Excellent Education, https://all4ed.org/issues/high-school-graduation-rates/. Accessed 12 Jun 2019.

“Bachelor’s Degree or Higher, Ages 25-34.” Greater Louisville Project: Advancing a Competitive City, http://greaterlouisvilleproject.org/factors/bach-degree-young/, Accessed 9 June 2019.

“Best College Majors for Highest Paying Jobs: 2018 Edition” Get Educated, 2018, https://www.geteducated.com/career-center/best-college-majors-highest-paying-jobs, Accessed 10 June 2019

Boston Private Industry Council. Boston Private Industry Council, https://www.bostonpic.org/. Accessed 12 Jun 2019.

“Boston Private Industry Council 2018.” Boston Private Industry Council, 2018, https://www.bostonpic.org/assets/resources/2018-Annual-Report.pdf, PDF File. Accessed 12 Jun. 2019.

Brown, Rachel. “Social Inclusion Best Practices: Forest City Washington.” NAIOP Commercial Real Estate Development Association. NAIOP, 2016, https://www.naiop.org/en/Magazine/2016/Spring-2016/Business-Trends/Social-Inclusion-Best-Practices. Accessed 14 Jun. 2019.

“Capital Area College Tech Prep Consortium.” Austin Community College. Austin Community College District, 2011, https://www.austincc.edu/catpc/educators/documents/ACC_TPAnnualReport11_I.pdf, PDF File. Accessed 12 Jun 2019.

“CEO Benchmarking Report: CEOs reveal what keeps them up at night.” The Predictive Index, 2019, https://resources.predictiveindex.com/ebook/ceo-benchmarking-report-2019/, Accessed 10 Jun 2019.

“Changing Lives.” 2018 Skillpoint Alliance Annual Magazine. Skillpoint Alliance, 2018, https://drive.google.com/file/d/1GRDCWYk0TWkylGw5pZle3E-wUTslTarO/view, PDF File. Accessed 12 Jun. 2019.

Cox, Jeff. “The U.S. labor shortage is reaching a critical point.” CNBC, 5 Jul 2018, https://www.cnbc.com/2018/07/05/the-us-labor-shortage-is-reaching-a-critical-point.html, Accessed 10 Jun 2019.

Dunkelberg, William and Holly Wade. “NFIB Small Business Economic Trends.” National Federation of Independent Business, Apr 2019, https://www.nfib.com/assets/SBET-April-2019.pdf, PDF File. Accessed 10 Jun 2019.

Forest City Washington Workforce Intermediary Digest (Draft 2)

Forest City’s Diversity Programs — Seeing the Big Picture: Executive Summary

“Greater Louisville Education Commitment.” 13 May 2010, http://www.55000degrees.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/05/Greater-Louisville-Education-Commitment.pdf, PDF File. Accessed 9 June 2019.

Gordon, Edward. America’s Meltdown: Why We Are Losing the Skills Wars and What We Can Do About It. A White Paper Presented at the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, Washington D.C., 2001.

“Louisville sets new record in education attainment.” LouisvilleKy.gov, 25 Oct. 2016, https://louisvilleky.gov/news/louisville-sets-new-record-education-attainment, Accessed 9 June 2019.

Metropolitan College. UPS, University of Louisville and Jefferson Community and Technical College, 1999, https://metro-college.com/. Accessed 13 Jun. 2019.

National Center for Education Statistics. “Skills of U.S. Unemployed, Young, and Older Adults in Sharper Focus: Results from the Program for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies (PIAAC) 2012/2014.” U.S Department of Education, Mar 2016, https://nces.ed.gov/pubs2016/2016039rev.pdf, PDF File. Accessed 12 Jun 2019.

National Fund for Workforce Solutions. National Fund for Workforce Solutions, https://nationalfund.org/. Accessed 8 July 2019.

Philadelphia Academies Inc. Philadelphia Academies, Inc, 2015, https://academiesinc.org/. Accessed 12 Jun 2019.

Rapacon, Stacy. “25 Best College Majors for a Lucrative Career.” Kiplinger, 5 Feb. 2019, https://www.kiplinger.com/slideshow/business/T012-S001-best-college-majors-for-a-lucrative-career-2019/index.html, Accessed 10 June 2019.

“Research Reveals Boy’s Interest in STEM Careers Declining; Girls’ Interest Unchanged.” Junior Achievement USA. Junior Achievement and Ernst & Young LLP, 2018, https://www.juniorachievement.org/web/ja-usa/press-releases/-/asset_publisher/UmcVLQOLGie9/content/research-reveals-boys’-interest-in-stem-careers-declining-girls’-interest-unchanged, Accessed 12 Jun 2019.

Seattle Jobs Initiative. Seattle Jobs Initiative, http://www.seattlejobsinitiative.com/. Accessed 8 July 2019.

Skillpoint Alliance. Skillpoint Alliance, 2018, http://skillpointalliance.org/. Accessed 12 Jun 2019.

Strauss, Valerie. “Hiding in plain sight: The adult literacy crisis.” The Washington Post, 1 Nov. 2016, https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/answer-sheet/wp/2016/11/01/hiding-in-plain-sight-the-adult-literacy-crisis/?utm_term=.c553d15246f4, Accessed 12 Jun 2019.

Unique Staffing Scope of Work for Brookfield Properties—Thompson Hotel

WRTP | Big Step. First Station Media, https://wrtp.org/. Accessed 8 July 2019.

John R. Fleming, Jr.

John Fleming is a seasoned executive and consultant with over 30 years of experience in creating and implementing innovative marketing and workforce solutions to challenging business problems. John has developed and implemented an integrated marketing and training system for 13 western states that trained over 2000 sales representatives. He has introduced and facilitated marketing management development programs for over 100 small business managers.

John has developed and led demand-side community and business initiatives in information technology, banking and finance, healthcare, building trades and engineering that has connected over 1,400 “harder to serve” candidates in employment. His clients for these services include Dollar General, Fannie Mae, Anacostia Waterfront Corporation, the Office of Deputy Mayor for Planning and Economic Development for the District of Columbia, Forest City Washington and Churchill Downs.

John leads a Service Disable Veteran Owned Small Business (SDVOSB) with a Secret Clearance that has placed current and dislocated workers with Humana, WellPoint, National Patient Account Services, Measured Progress, US Bank, PNC Bank and Serco N.A. (a large Department of Defense contractor). This firm also supported military activities of the Joint Personal Effects Depot at Dover Air Force Base Dover, Delaware.

John has been Vice President of Human Resources and Vice President of Marketing for Anthem Blue Cross Blue Shield. Prior to Anthem, John was Director of Marketing for Metropolitan Life.

John is a retired U. S. Army Lieutenant Colonel. He has commanded a combat unit and received the Bronze Star, Meritorious Service Medal and Army Commendation Medals.

John is a native of Ashland, Virginia and a graduate of Virginia State University with a Bachelor’s and Master’s of Science degrees in Psychology. John also has an Associate’s degree in Marketing from Sinclair Community College in Dayton, Ohio. He has attained the Chartered Life Underwriter (CLU) designation and is a graduate of the U. S. Army’s Command and General Staff College.

Lauren S. Prince

Lauren Prince is a rising second year (sophomore) at the University of Virginia. She is a recipient of the University Achievement Award and hopes to major in Political and Social Thought with a minor in Latin American Studies. She plans to attend law school after finishing at the University of Virginia.

Lauren graduated Summa Cum Laude from her high school in the top 1% of her class. Throughout high school and into college, Lauren has been involved in a variety of extracurricular activities including serving as president of eco club, class secretary, and co-founding an online feminist magazine titled She Persisted Magazine. During her first year of college, she worked in the Religion, Politics, and Conflict Department as an intern for the Trump Initiative. Additionally, she writes for the University’s online organization, The Virginia Review of Politics. In her free time, Lauren loves to read and discuss issues such as climate change and human rights.

[1] See “A Work in Progress: Case Studies in Changing Local Workforce Development Systems” The Annie E Casey Foundation, 1995

[2] America’s Meltdown: Why We Are Losing the Skills Wars and What We Can Do About It, 2003