About Workforce Intermediaries

The History

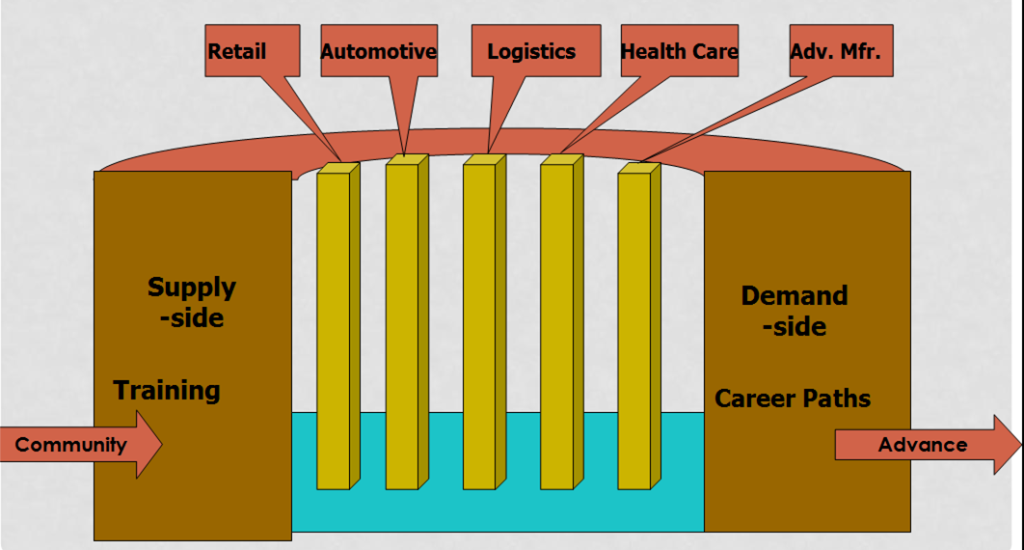

Workforce Intermediaries (WI) grew out of the need to bridge the gap between community organizations and educators who trained people to work, and businesses in need of workers. The traditional thinking is for organizations to train candidates and present them to employers. However, businesses want employees when there is a need. Often candidates are delivered to employers without regard to the business corporate culture or business cycle. The intermediary’s role is to “bridge” the timing and information gap and align employee preparation and training to employer need, thereby creating the optimal connection between the demand and supply sides of the world of work.

Build a Bridge to Tomorrow, Today

SUPPLY SIDEFocus

|

DEMAND SIDEFocus

|

Four Workforce Readiness Strategies

Four Workforce Readiness Strategies

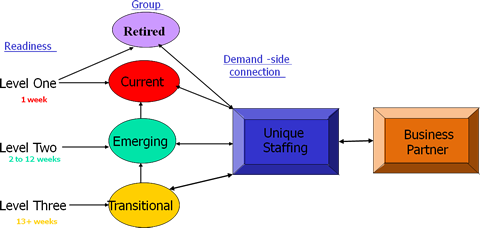

Cities such as Memphis, Tennessee and Austin, Texas as well as Louisville, Kentucky have divided candidates into to 4 workforce groups. Each group must have a strategy centered on the time it takes to prepare for a new work assignment. Senior citizens and those currently working (including those recently displaced) have the basic skills. They may need one week to become ready for a new work assignment. The strategy necessary for these two groups must include affordable opportunities to learn new skills or to keep skills current with the changing needs of employers. Those coming out of high school and to some extent college (the emerging workforce) need 2 to12 weeks to become ready. They need to learn the “language” of work as well as the culture of specific industries. The strategy necessary for this group must include real world experiential education, expansion of school-to-work initiatives, and curriculum designs that meet the needs of employers. Those who are drop-outs, returning citizens or ex-offenders, immigrants and welfare recipients (transitional workforce) need to “build” a work history as well as being prepared for a work assignment. They will need more than 12 weeks to become ready. The strategy necessary for this group must include short-term hands-on, real world training that can result in employment opportunities in a short period of time (part-time or temporary employment). The training must address the basic soft skills and technical hard skill deficiencies that these individuals have, and find innovative methods to deliver these skills. Below is an illustration of the workforce groups:

SUMMARY

- In both demand and supply-side examples, a WI should have as its partners community colleges and universities, technical/vocational schools, workforce development organizations (to include community and faith-based organizations), and business partners (including the Chamber of Commerce, and trade and business associations) who will define the employment need. Typically, the WI is not a policy-making organization, such as federally-supported Workforce Investment Councils or the local Chambers of Commerce. Instead, it is an on-the-ground, “in the trenches” organization that coordinates the workforce activities to respond to upcoming employment demand.

- Robert Giloth (editor of Workforce Intermediaries for the Twenty-First Century, 2004) indicates that “Great need exists to build regional and national infrastructure to support the development and expansion of WI’s, including venture funding for growth, benchmarking, human resource development, ongoing learning and public policy. This infrastructure must be aligned with the goals and strategies of public workforce development systems.”